Psychohistory is a relatively new and controversial discipline that gives the past more sense and perspective by looking through the powerful lens of psychological knowledge.

Psychohistory also explores how shifts in consciousness and national mind-sets create ways of thinking about the world. Psychohistory analyses societies rather than individuals. Sometimes it may highlight how people collectively collude to avoid “inconvenient truths” or protect a favourable identity.

Psychohistory can sometimes find the missing piece in the puzzle or discover what an emerging zeitgeist might reveal. An evolutionary and crucial tool, it can analyse political systems and point towards a needed direction.

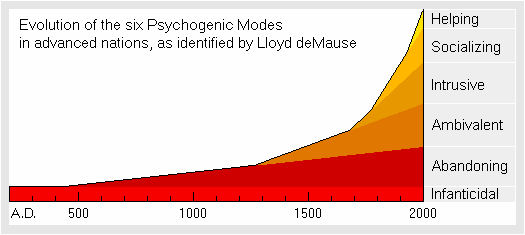

Image courtesy of WikiCommons

How does Psychohistory work?

- Psychohistory follows how individual attitudes shaped under stress or trauma morph into group psychopathology, which over time become crystallised as a group identity.

- Psychohistory reveals how groups tend to scapegoat voices that do not collude conform to consensus values.

- Psychohistory asks uncomfortable questions, such as: “Under what conditions would this crazy-seeming behaviour make sense?” An example is the outbreak of mutism among shell-shocked WW1 veterans: what they had witnessed was unspeakable, but they were treated as hysterical.

- Psychohistory employs systemic thinking over individualised apportioning of blame. How would it respond to the repeated murder of children in their schools by apparently mad individuals, for example? It might hear an expression of the problems of innocence and violence spoken by an unconscious but active instrument of the society.

- Psychohistory takes soundings from art and literature of the period examined. This tends to reveal both conscious and unconscious voices within a society, and points both to what the society may not yet be able to recognise and also towards emergent zeitgeists or paradigms.

Why is Psychohistory is controversial?

It is controversial because linking psychology, history and politics is not encouraged by the isolated specialised disciplines, especially not by the professional psychological press, which in Britain bans it. Politicians are skeptical of what they term ‘psycho-babble,’ and the media have an ambivalent attitude, pouncing on juicy ideas when it suits them, but avoiding deeper perspectives. Wounded Leaders is an attempt to address this balance.

In a 1994 New Yorker interview with founder of the Institute for Psychohistory, Lloyd DeMause, the journalist wrote:

To buy into psychohistory, you have to subscribe to some fairly woolly assumptions, for instance, that a nation’s child-rearing techniques affect its foreign policy.

Ironic as this comment is, it is both precise and correct. It is exactly the kind of argument that should be taken exceedingly seriously, even it is not a popular perspective, and why a psychological approach to our politics is inescapable and long overdue.

Some specific Psychohistorical revelations in Wounded Leaders

Wounded Leaders introduces the understanding that, due to the fear that the French Revolution caused in the British Establishment, Enlightenment thinking developed in a particular way, designated here as The Rational Man Project. The British Empire ran on a combination of fear and grandiosity – immature egoic qualities. It based it success on the ability to convert what psychotherapy has identified as ego-defence mechanisms, such as dissociation, projection, objectification and normalisation into values.

This conjuring trick allowed the elite to colonise and exploit the New World without conscience and to create an industrialised process to replicate themselves that they still believe in. Wounded Leaders asserts that Britain is still in the grip of this spell, still in a trance, here called The Entitlement Illusion. Wounded Leaders points to the elephant in room, announces that out the Emperor’s new clothes reveal all.

Wounded Leaders proposes that British politics, including the nature of our leaders, the entry of women into parliament, the class-structure of our society, the shape of our education system, the attitudes to children and parenting, the embedded drive to privatisation, and even the design of the House of Commons, are all still shaped by an unique elitist and out-dated system of private education based on taking children out of the home.

Wounded Leaders recognises that the normalised use of dissociation, projection and objectification amongst the British elite does untold transgenerational damage to families, preserves an anachronistic class divide and fear-driven attitudes not found anywhere else in today’s world. This prevents the political system from becoming nationally relevant and ensures that the quality of leadership emerging will be out of step with current needs.

Wounded Leaders introduces a new kind of critique. Rigid Enlightenment thinking, where all disciplines are separated and out of dialogue with each other, is the dominant mode of The Rational Man Project. At this crucial point in the world’s history, many cutting-edge thinkers believe that new interdisciplinary approaches (this book is one tiny example) are essential to think one’s self out of the trap of hyper-rationality, which is anachronistic and therefore anti-evolutionary.